We’ve just published a paper on how a protein’s ability to form hydrogels allows cells to sense and respond to stress.

A bit of background

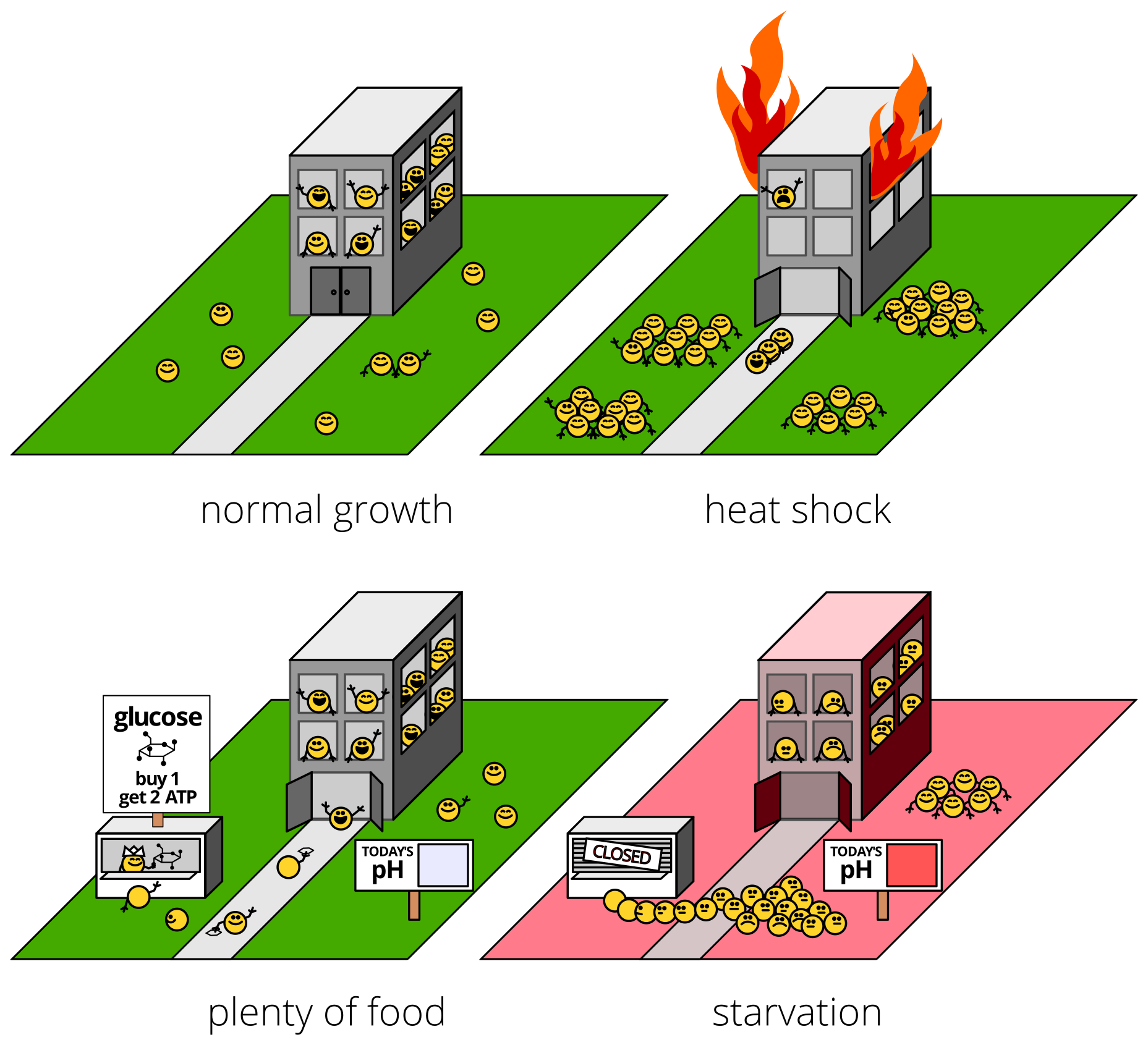

Like us, cells react to stresses like heat, starvation, and poison. All these stresses cause clumps of molecules to form inside cells. This clumping—aggregation—looks like damaged proteins sticking together. But in our last paper, we showed that instead, these clumps look like they’re a cellular response, not just signs of damage. (See our blog post on it.)

We’re going to go back to the Cellular Institute with its manicured grounds and main building. Happy workers (proteins) go about their often inscrutable business.

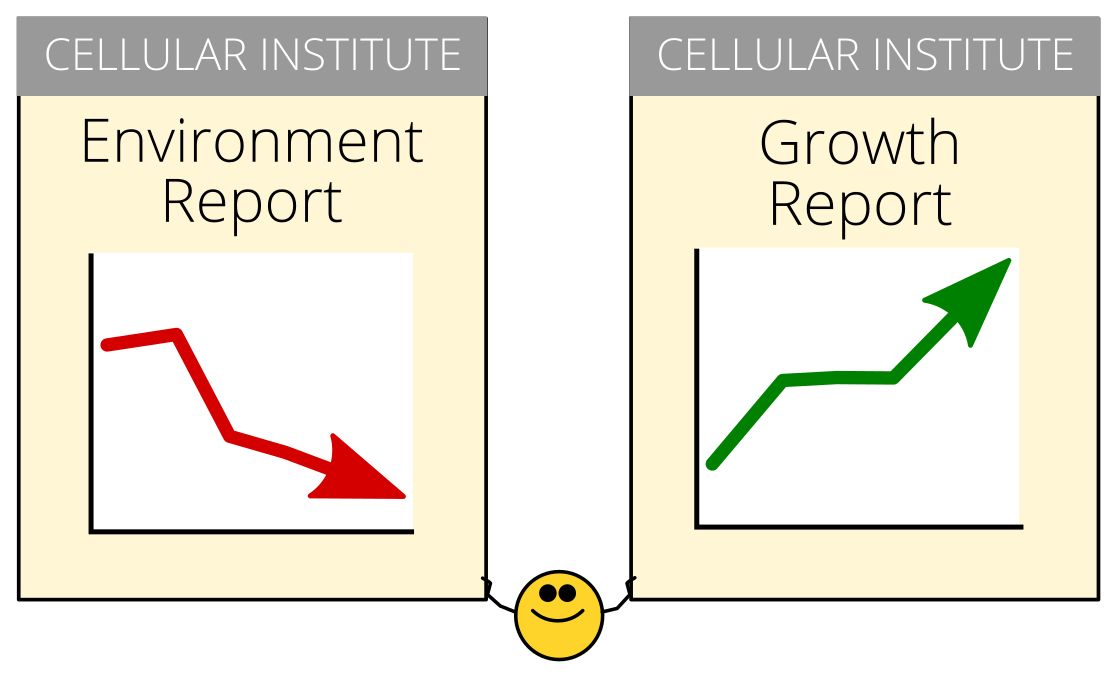

The Institute is constantly dealing with awful changes in its environment. The mission is to survive, even to keep growing, during those tough times.

The picture that came out of our earlier study suggested that, overall, the clumping in cells was an organized, reversible process, consistent with a coordinated effort to survive tough times.

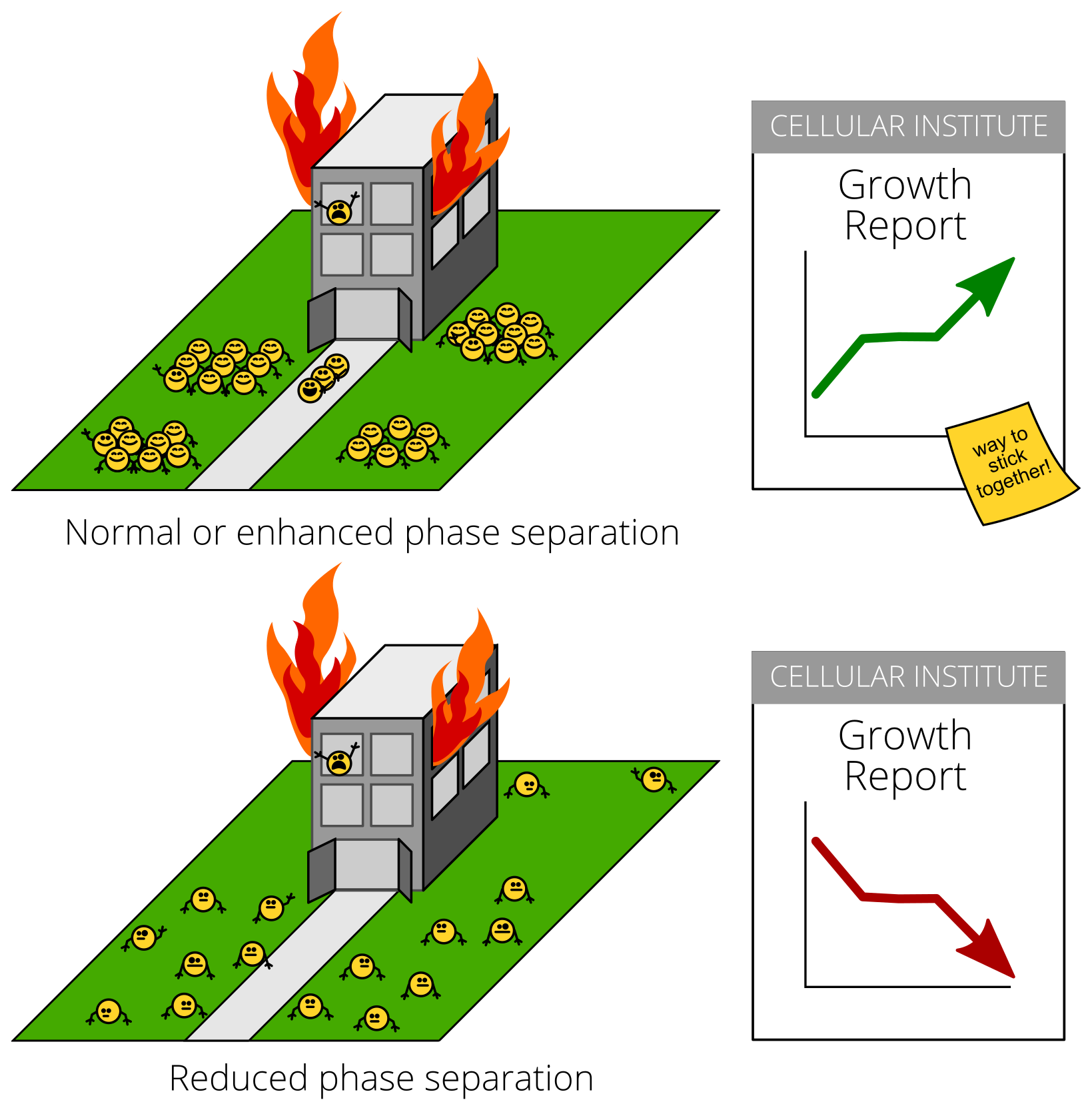

But what about for specific proteins? How can you tell if clumping is stress-inflicted damage or an adaptive response? A key test is to see what happens when you stop the clumping during stress. Stopping damage during stress should make cells healthier. Stopping an adaptive stress response, on the other hand, would make cells sicker.

Doesn’t sound too complicated

Easy for you to say, headline! In our study, we had to first find a protein that formed clumps during stress, then figure out how to control its clumping without screwing up a bunch of other stuff (which involved quite a bit of figuring out why it formed clumps, physically, and which bits of the molecule were responsible).

Doing all that required working on the protein in isolation in a test tube, so then we had to put the protein back into cells to see if it worked the same way. Finally, we could expose those cells to stress and see how they responded.

What did we do?

We picked out a specific protein that formed clumps during stress: poly(A)-binding protein, which is nicknamed Pab1 in baker’s yeast, our beautiful and hardy model organism. (Relatives of Pab1 are found in essentially every cell that has a nucleus, from plants to parasites to people.) We purified Pab1, put it in a dish, and exposed it to the same intracellular conditions that follow stress and are thought to cause clumping, heat and pH.

Yeast cells like to live in acidic (low-pH) environments, but keep their insides at neutral pH. When cells get stressed, their internal pH drops, becoming more acidic. That, others have argued, might cause clumping during non-heat stresses like starvation.

What did we find?

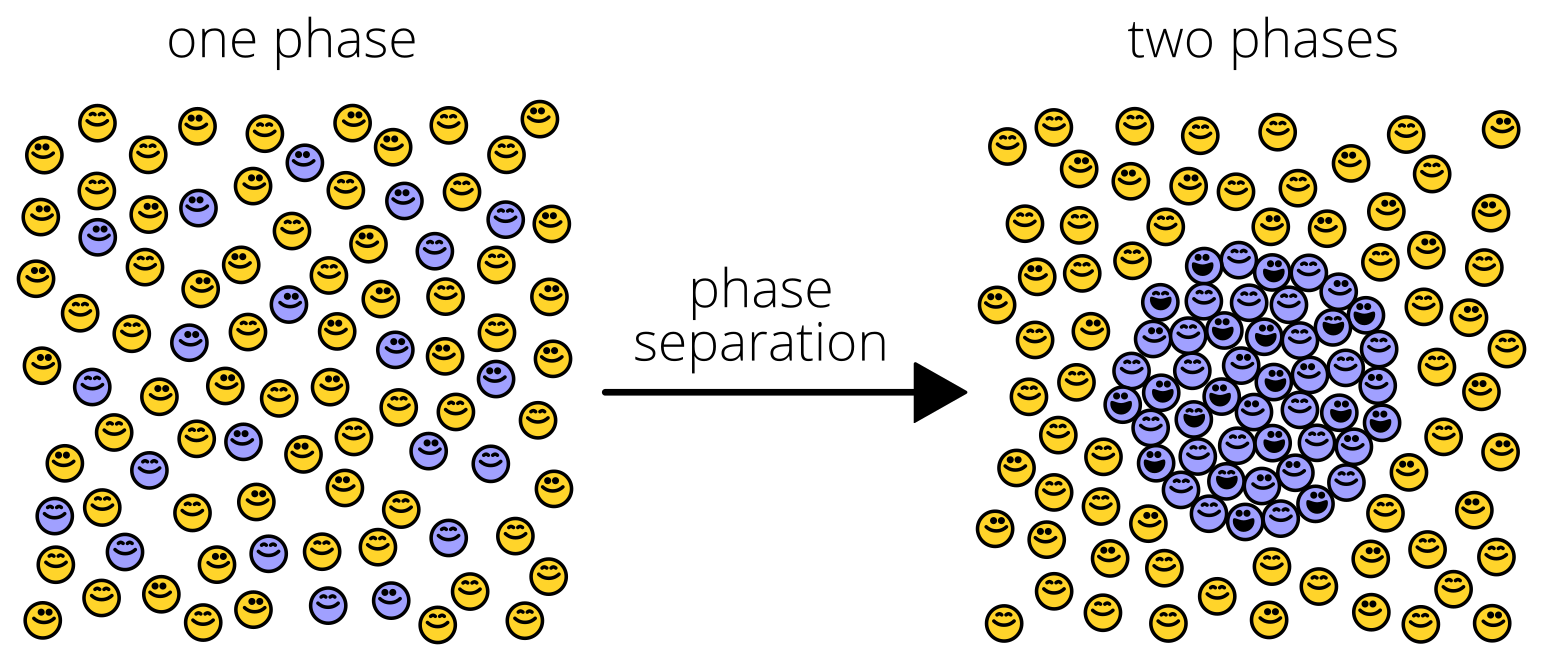

First, we discovered that Pab1 “clumping” was something rather specific and wonderful: phase separation into hydrogel droplets.

Phase separation is like a flash mob. Under certain conditions, suddenly, from a mixture of two types of molecules, one type surges together, separating from the other (“demixing”) like oil droplets from water. Bunches of recent studies have shown proteins doing this trick, usually under exotic conditions.

Pab1 phase-separates in response to both pH and temperature, right at the stress-associated ranges of each one. It’s one of the coolest results in the paper: Pab1 is an extraordinarily sensitive sensor of stress, particularly temperature. You might be surprised to know that how yeast cells sense temperature has been a bit of mystery…

Back into the cell

We figured out a way to make Pab1 phase separate at lower or higher temperatures. Remember our key test? That let us make cells with proteins that couldn’t get together during stress. And guess what we found?

Cells with Pab1 molecules that didn’t stick together during stress couldn’t grow during stress. This happened during heat shock, and during starvation, too!

Ultimately, it’s about fitness

There’s been a bunch of beautiful work on phase separation, hydrogel formation, and other quinary phenomena. (Quinary, a term introduced by Stuart Edelstein, refers to a step beyond traditional quaternary structures to structures involving undefined numbers of molecules.) But showing that these phenomena are actually good for cells, as opposed to just gorgeous curiosities, has been challenging. Pab1 delivered for us!

Dive in!

This paper was five years from initial discovery to publication. There’s a lot in there (though the reviewers wanted oh so much more!). For experts, our results are full of surprises. First author Josh has blogged about some of the biophysical aspects and co-first author Chris has blogged about the in vivo aspects.

And there’s much more to do. How, exactly, does Pab1’s phase separation help the cell? We share some ideas in the paper. How, exactly, does Pab1 sense temperature and pH? Watch this space as the story continues to, well, come together.