Hi, I’m Chris. I’m a student in the Drummond lab and coauthor on the paper “Stress-Triggered Phase Separation Is an Adaptive, Evolutionarily Tuned Response.” When presenting this work, I’ve been asked a few questions repeatedly that I will answer in a FAQ section. I’ll also share an anecdote about the challenges of delineating Pab1’s role in the stress response from its many other functions. I hope the story emphasizes the importance of endogenous protein expression levels.

FAQs:

The ΔP yeast strain grows better at high temperature than the other demixing-impaired mutants – what gives?

How can a few point mutations in the P-domain have a greater fitness effect than deleting the domain wholesale? In figure 6F, when we compare the growth at 40° C of yeast expressing Pab1 variants; mutants “MV->A” and “MVFY->AGPNQ” show a major growth defect. These mutants show a greater defect than the strain expressing Pab1ΔP. This is result is most easily rationalized through the lens of demixing: Pab1ΔP demixes more robustly than either of the mutants; therefore it grows more robustly at high temperature. Figure 6G illustrates the relation between growth and Pab1 demixing. The related question, “how can a few point mutations have a greater effect on demixing than deleting the domain wholesale?” remains open. Josh discusses this point in greater detail in his blog post.

How do mutations to the P-domain affect stress granule formation?

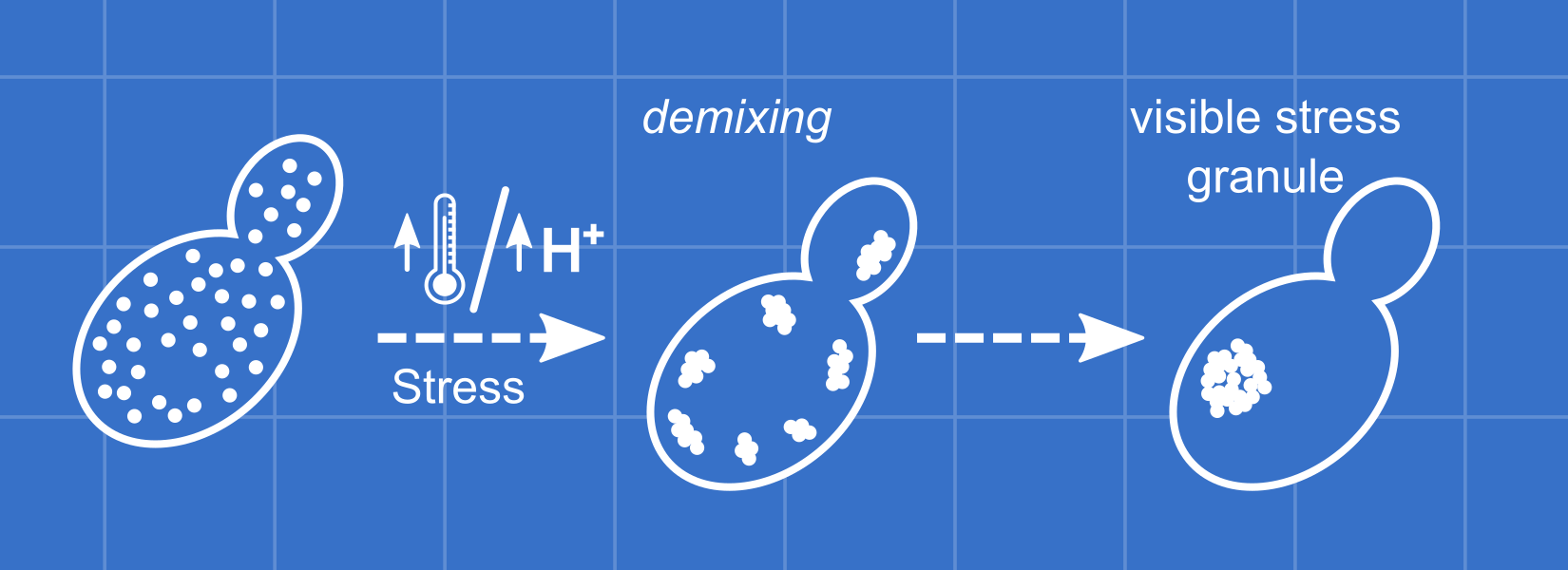

I don’t know. The stress used in figure 6D to trigger Pab1 demixing is too mild to elicit Pab1-marked stress granules in wild type cells (figure 1A). Moreover, while stress granules are easily observed, it is not clear that they are the physiologically functional species. Here, we make the case that perturbing demixing of Pab1 is sufficient to affect physiology. In fact, I favor the hypothesis that quinary assemblies and stress granules are related, but separable phenomena. Pab1 forms sedimentable quinary assemblies in the absence of visible focus formation. Conversely, HSP104 is an example of a protein that colocalizes with stress granules, but isn’t sedimentable.

Is the assembly of other proteins perturbed?

Yef3 is another protein that forms sedimentable species during mild stress conditions. Figure S5 indicates that demixing of Yef3 does not vary between P-domain mutants. However, it is possible that demixing of one of the other ~150 heat-assembling proteins is affected. At its core, this question is about the mechanism of formation of large cellular assemblies. Are all proteins demixing autonomously, or can one protein recruit another to these structures? Is RNA binding sufficient to recruit some proteins? Is recruitment stress specific?

What is going on with RNA?

Right? In vitro we show the following: RNA is not necessary for Pab1 demixing (fig 2E), RNA actually inhibits demixing (fig 2C); and short poly(A) sequences are released during demixing (fig 2A). One interpretation is that demixing is dominated by protein-protein interactions and these interactions are mutually exclusive with RNA binding. In vivo we show that heat-triggered sedimentation of Pab1 is RNase1 insensitive (fig 1B). This result is consistent with the in vitro results, though other interpretations are possible. This model predicts that demixing of Pab1 and poly(A)-positive RNA are not mechanistically connected. I find this unintuitive, but testable.

You speculate about Pab1 as a translational regulator of the stress response. How much is speculation?

If you’re curious about the mechanism by which Pab1 demixing affects stress tolerance, then come to my talk at ASBMB “Translation of heat shock proteins is regulated by poly(A)-binding protein assembly.” Its on Sunday April 23 2017 during the Protein folding, Aggregation, and Chaperones session; or come see the poster later.

Make happy yeast:

Pab1 is an essential gene with a role in many cellular processes. If one wishes to make mutations, delete then replace isn’t an option. Other work has successfully expressed Pab1 from a plasmid. However, cells are very sensitive to Pab1 expression levels – consistent with its known autoregulatory expression mechanism. My first attempt to modify the Pab1 P-domain was with a construct that replaced the native genomic 3’ UTR with a KanMX selectable marker. I also made the control strain with the same marker, but preserved P-domain. The control strain grew slowly and at 30°C and expressed Pab1 at ~20% the wild type. Reduced expression is problematic because demxing is concentration dependent; similarly, over-expression can lead to demixing artifacts. Worse, the proteome of this control strain resembled that of stressed wild type cells, including high chaperone expression. Ultimately, I developed the serial transformation strategy described in the methods (and another blog post). The resulting strains have no selectable markers, native 3’ UTRs, and no extra nucleotide scars. This manor of strain construction solved the reduced Pab1 expression and slow growth problems. Now, I am able to discern the relation of assembly and the stress response, without conflation of growth rate effects.