By Sammy Keyport and Caitlin Wong Hickernell

This article was originally published on the Illinois Science Council Blog.

Temperature has a fascinating and complex relationship with biological systems. Intuitively, extreme temperatures can be harmful to living organisms. Anyone who has gotten a sunburn or frostbite before knows what we’re talking about. Because of this, when scientists study how temperature interacts with organisms, they often classify temperature as a potential “stress.”

Yet, temperature is much more than just a potential source of harm. For organisms that lack ears or eyes, temperature is one of the most important sources of information about their surroundings. Temperature is a signal to organisms that their environment is safe or dangerous, allowing them to launch an informed response.

Humans process temperature and respond reflexively, sometimes by shivering in cold weather or by removing a hand from a hot stove. Similarly, a whole range of organisms have intricate temperature-sensing systems. These systems process temperature, along with other environmental signals, to gather information about an environment and help organisms adapt and survive. Thus, temperature plays a crucial role in transmitting life-saving information to biological systems, from helping human cells detect an infection, to aiding bloodthirsty mosquitoes in finding a source of food, to telling microbes when to reproduce, to determining sex in fish.

Temperature Can Signal for Help

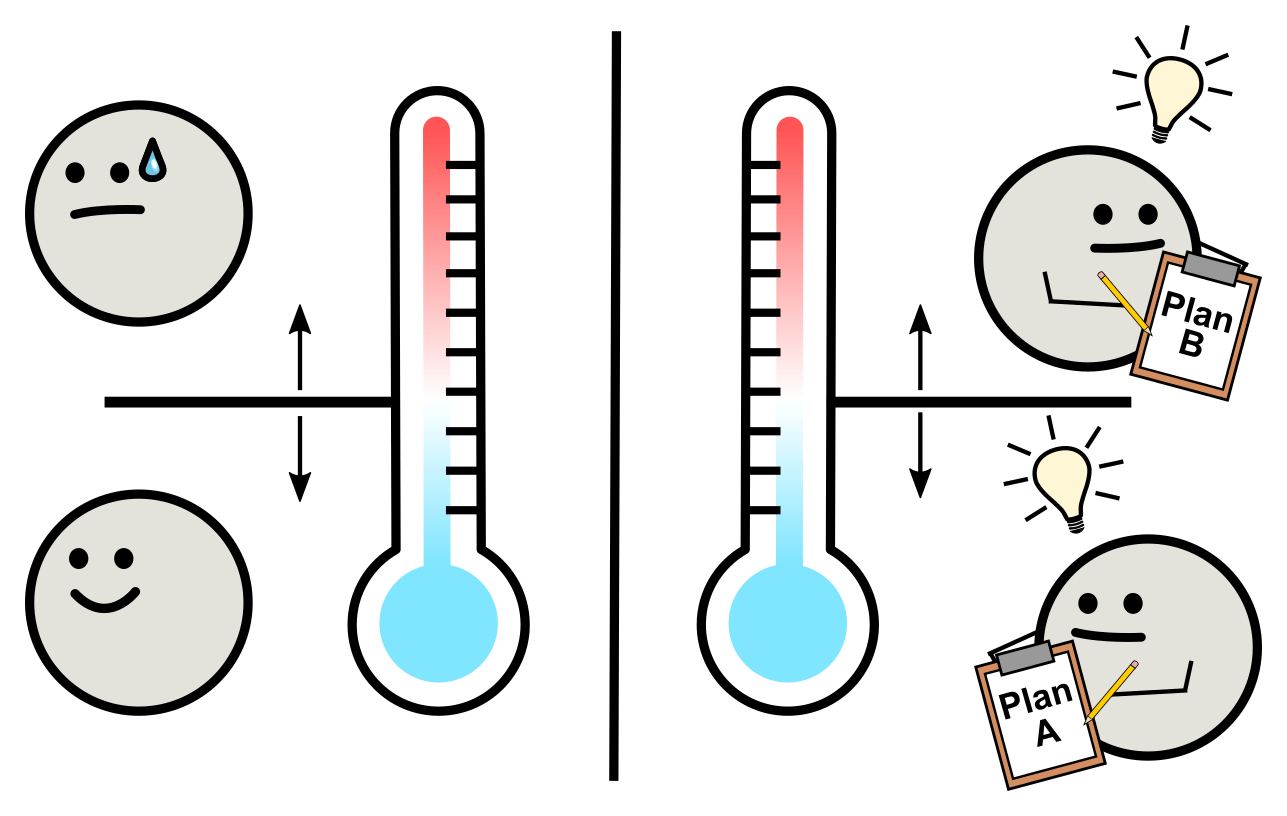

When your body temperature reaches just a few degrees above 98.6°F, you may feel like your body is malfunctioning. However, a fever is actually your body’s planned response to a harmful pathogen. A fever signals to organs and tissues that you are fighting an infection, which ultimately leads to responses that help you recover from an illness. Immune fighter cells detect elevated temperature and produce chemicals, some of which directly kill the pathogen and some of which recruit other immune cells.

Activating immune cells in response to a fever helps you recover from an infection, but if your immune cells become activated in the absence of a temperature change, they could cause damage to tissue by killing healthy cells. In fact, unchecked immune cell activation leads to many autoimmune disorders like Type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Consequently, temperature is a critical signal for our bodies, but it must be interpreted correctly to truly help us survive.

Temperature Can Signal the Presence of Food

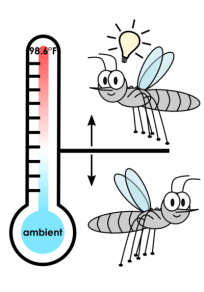

Did you know only female mosquitoes bite? That’s because they need nutrients found in your blood to develop their eggs. In fact, male mosquitoes generally avoid humans. But how do female mosquitoes know where to find us?

Mosquitoes are attracted, first and foremost, to carbon dioxide, which humans constantly exhale. Female mosquitoes also detect movement, odor, and, importantly, heat to find their lunchtime snack. In fact, mosquitoes detect temperature differences as small as a few degrees and avoid objects that are hotter or colder than normal human body temperature. In this case, temperature is among the signals of human blood meal that female mosquitoes detect to navigate to their food.

Temperature Can Signal When Cells Should Divide

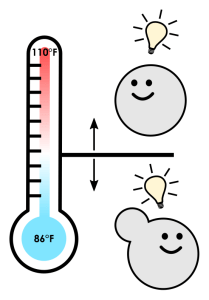

The dream of a unicellular yeast is to become two yeast cells. Thus, yeast cells will divide and reproduce until they run out of food or room. However, when yeast cells experience temperatures that they find uncomfortable, they divide much more slowly. If yeast have a single-minded focus on cell division, why would cell division ever slow down?

Some scientists have speculated that high temperatures stress and damage their internal machinery. However, based on recent research in our lab, we’re starting to realize that yeast machinery is not breaking down. In fact, the slower cell division might be not be an unintended consequence, but rather, a planned response.

But a planned response to what, exactly? To understand that question, we need to take a bird’s-eye view of yeast, literally. Yeast will grow happily on grapes, where they are fair game for hungry birds. Scientists have shown that yeast can survive being eaten, digested and passed by a bird, which makes birds their primary form of long-distance transportation. Interestingly, a bird’s stomach is the same temperature that causes yeast divide slowly. Putting this together, our lab thinks that warm temperatures might tell yeast that they have been eaten by a bird and that they are currently residing in its stomach. With this information, yeast can shut down their dividing machinery to save energy and resources until they reach a more hospitable environment. Thus, the yeast’s ability to sense temperature and shift into a frugal survival mode is critical for their survival as a species.

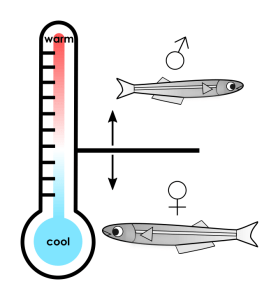

Temperature Can Determine Sex

For Atlantic silverside fish, the temperature of a developing egg determines whether the fish becomes male or female. This method of sex determination is drastically different from humans, whose sex is determined by chromosomes. It turns out that this temperature-dependent development is crucial for this species of fish to survive. When female fish are born early in the spring and have time to grow larger, they can hold more eggs. The population of silverside fish therefore benefits from having females born first so they have more time to mature. For this reason, eggs incubated in early-season cool temperatures are predominantly female, while eggs hatched in late-season warm temperatures are predominantly male. (Male fish produce the same amount of sperm regardless of their size, so it doesn’t matter as much when they’re born.) Only 0.04% of eggs become adults, so a small increase in a female fish’s size can have huge consequences for the fish population. In this way, sensitivity to ambient temperature is crucial for Atlantic silverside fish to survive another year.

As we think about the effects of climate change, we should consider animals such as these fish, whose sex ratios vary depending on the seasonal temperature. Rising temperatures could cause fewer silverside females to survive each year, leading to a significant drop in the population. This effect could compound over years, disrupting not only this species of fish but other animals in its ecosystem.

Research Tackles Unanswered Questions About Temperature

A variety of organisms rely on temperature to make decisions about how to best adapt to their environments. However, there are still many unanswered questions about the relationship between life and temperature. For example, how exactly do organisms “sense” temperature on a cellular level? What are their internal thermometers and how do they work? These questions are inspiring for research scientists like us. As we think about the ever-increasing likelihood of a warmer world, we are motivated by the fact that solutions often come from unexpected places. We are hopeful as we look back on the resilience of life through evolutionary time and look forward to a future of greater understanding.